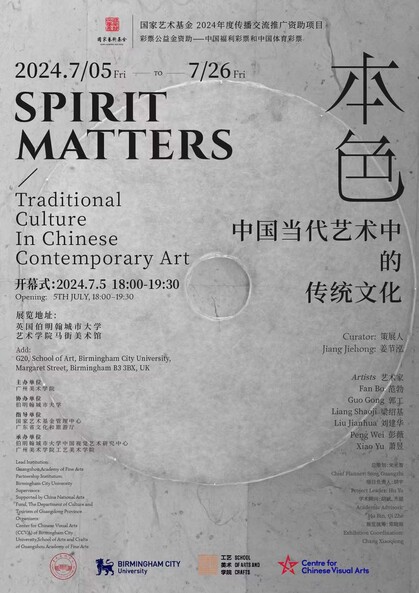

Group Exhibition G20, School of Art, Birmingham City University, U.K., Margaret Street, Birmingham B3 3BX

Curator: Jiang Jiehong

Artists: Fan Bo, Guo Gong, Liang Shaoji, Liu Jianhua, Peng Wei, Xiao Yu

Spirit Matters

Throughout the 20th century, China experienced dramatic social and political transformations. During the 1950s, a wave of major cities were industrialised, and during the latter half of the 1960s and into the 1970s, historical architecture and cultural heritages were severely neglected or destroyed. In particular, the late 1960s provided an extraordinary example of political mobilisation directed against material and cultural vestiges. Soon after, the Open Door policy (1978) instigated economic reform, while Western culture began to permeate once again into everyday Chinese life, initiating a gradual ‘renovation’ towards an ‘internationalised’ style of living. Today, in China, the traditions of arts and craftsmanship have been interrupted. The consequence of this unique situation is a state of cultural anxiety, whilst contemporary art stands in a pioneering role taking the challenges through critical reassessment, as well as through their endeavour of reconnecting, reconciling and repairing the somehow distant traditions.

In the autumn of 2018, we curated and hosted an exhibition Everyday Legend: Reinventing Traditions in Chinese Contemporary Art at the School of Art, as one of the outputs of our research project funded by the Leverhulme Trust. Following the success of the exhibition and in collaboration with Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, we present this show, as a continuous discussion around Chinese traditions in the context of contemporary art. Presenting works of painting, installation, and video by six leading Chinese artists, Fan Bo (b. 1966), Guo Gong (b. 1966), Liang Shaoji (b. 1945), Liu Jianhua (b. 1962), Peng Wei (b. 1974), and Xiao Yu (b. 1965), this curatorial project focusses on ‘matter’, examining how these various materials that are rooted in Chinese traditional culture can be examined and reinterpreted in contemporary art practices. Six different ‘matters’ have been employed respectively by the participating artists – namely, ceramics, silk, bamboo, paper, herbal medicine and wood – as inherently ‘Chinese materials’ with their particular aesthetic qualities and symbolic, spiritual significance.

Ceramics, perhaps one of the oldest materials of craftsmanship in China, has become the dominant language of Liu Jianhua’s artistic practice. When this type of material becomes a language, it does represent not only its materiality and the craftsmanship; but also, concurrently, it formulates a specific process of making, extending the physical to something spiritual. When a ‘Chinese’ material becomes part of contemporary artistic language, it not only contributes to a ‘semantic field’; ornate, simple or sophisticated; more importantly, the rules governing the intangible elements resulting from the traditional craft and production process constitute the overarching ‘grammar’ of this language. Liu’s installation simply shows piles of ‘sand’, around twenty of them, one of the most common materials, the remnants of which one can easily stumble upon in any construction site in urbanised China. In fact, Liu Jianhua changes the status of this humble material: they are not the sand used for construction and making, raw and inexpensive, soon becoming invisible in the final product. But instead, they are ceramics, pre-fabricated, in the shape of ordinary sand piles, through means of traditional firing techniques as exquisitely crafted pieces of art.

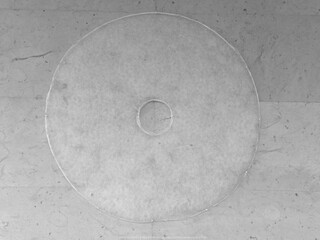

Returning to the point of origin of oriental textiles, or to their basic constitutive unit, Liang Shaoji’s language is silk, which can be equated with the expression of Chinese civilization from ancient times. Since 1989, the artist has committed his life to breeding and training silkworms to produce this organic material for art making. His artistic and philosophical contemplation on the topics of traditional culture and contemporary life are solely expressed through his understandings of the texture and physical properties of silk, and through his private communications with these remarkable larval-stage insects. Liang’s on-going work Tunnel is inspired by an archeologically excavated Western Han dynasty (202 BC – 9 AD) dress, a full garment made with finest and lightest silk more than 2,000 years ago, weighted only 49 grams. Mastering their biological rhythm and movement of spinning according to the designated position required for the artwork, the trained silkworms produced a series of translucent silk discs. To the artist, his silkworm is a collaborator in art production, a messenger to establish a dialogue across the millenniums, and an architect of a ‘tunnel’ for time travel adventure.

Bamboo has been favoured in literati painting and poetry since the Song dynasty (960–1279). It has played a central role in Xiao Yu’s work, not only as the subject per se, but also as the primary working material to set up a new point of departure for the artist’s further explorations of intuitive and bodily perceptions. In his work, this special plant, strong, tough and flexible, has been cut, twisted and inflected by human force to its absolute limits. The 2015 video work, Thinking Too Much That…, shows a section of a mature bamboo cane which is almost perfectly straight – the same thickness from end to end, strong and steady. In extreme slow motion, the bamboo perceptibly begins to tremble. It is being twisted. Following the unknown source of forcible tension, it cracks and distorts until – crushed, or transformed – it is broken down into fine strips and strings. At a pivotal point, the twist is slowly reversed, the broken is restored and the wounded is healed, as if the bamboo has regained its strength and power, ready for a new challenge.

In Fan Bo’s 2021 painting series, Heterogeneous Images: Mutation, Chinese herbal medicine carrying with its cultural and philosophical significance has been used to amalgamate oriental and western understandings on the present-day situations. The artist gives up his skilful realistic techniques he obtained after years of training, whilst the canvas becomes enlarged pages of his thinking, disclosing scribbled formulas, improvised notes and data, and illustrated human organs. Derived during the global pandemic, these signs and images from biological science unveil traces of confusion, hesitation, doubt, sorrow and agony through the process of reflections on disease, the fragility of life, divisive voices across the globe, and also, an uncertain future of our humanity. Envisaging such a complex web of ideas and struggles, compassions and conflicts in the contemporary society today, in Fan Bo’s paintings, herbal medicine is no longer a healing method, a mystery from China, but instead, it can act as a cultural ambassador, a diplomatic negotiator, or, as a prayer for peace.

Since a young age, Peng Wei was trained in Chinese traditional painting and calligraphy, where paper, invented in China’s Eastern Han dynasty (25 – 220 AD), is a vital material to support and present artistic expression. In her series of painting installations, Peng Wei invites us to revisit the everyday life of dynastical China, whilst various traditional buildings, literati gardens, pavilions and pagodas, women and men in costumes, are depicted in styles reminiscent of a scroll painting. And yet, rather than painting scrolls, they appear in the form of female mannequin busts. Those painted female ‘bodies’ display eventful spaces and spectacles in the past; stories and legends, to be observed in detail. In Peng Wei’s work, paper made with traditional techniques are first plastered onto the chosen mannequins, smooth or wrinkled, as the ‘skin’ of the ‘body’, and then, once dried, taken off from the bust. Traversing from two to three dimensional spaces, paper is used not only as a conventional medium for the painting, but as a material to construct the sculpture. While a mannequin is an artificial body, Peng Wei’s paper installation, in turn, becomes an ersatz mannequin presenting her imagined world – detached from banal existence, delicate, graceful, and ethereal.

In this exhibition, Guo Gong presents a scroll. His scroll however was not made with paper, but simply from a trunk of a pine tree. Through painstaking process of the making, the tree trunk was peeled slowly – one layer after another – almost like being tortured by a powerful apparatus, as if one attempted to explore and scrutinise anything hidden inside its body. When the entire piece of wood is unfolded, it remains a roll of blank sheet of more than five metres long and approximately a half millimetre thick, presenting no words in addition to the natural texture, as a determined statement of ‘confession’. In another work by the artist, wood can be transmuted into ‘metal’. He collected some waste reinforced steel bars from construction sites in the city; they had been deformed by unknown forces or reasons. The artist then faithfully copied the distorted shape of the selected reinforced steel bars by instead using blackwood. Inch by inch, precisely calculated, and section by section with almost no visible joint, only the most meticulous and skilful craftsmanship could realise the imitation. In the above two pieces of Guo Gong’s work, wood as a dominant material demonstrates its unique cultural spirit. If the former displays its openness, confidence, honesty and bravery, then the latter reveals the qualities of empathy, resilience and tenacity.

To our artists, what matters is not only the visual language and material, but also methodological approaches of their artistic practices. More importantly, through the making with the artistic investment, they are transformed beyond matter – illuminating the cultural traditions in the contemporary context, and extending the existing aesthetic imagination and the spiritual power inside the material forms.

Jiang Jiehong

May 2024, Birmingham