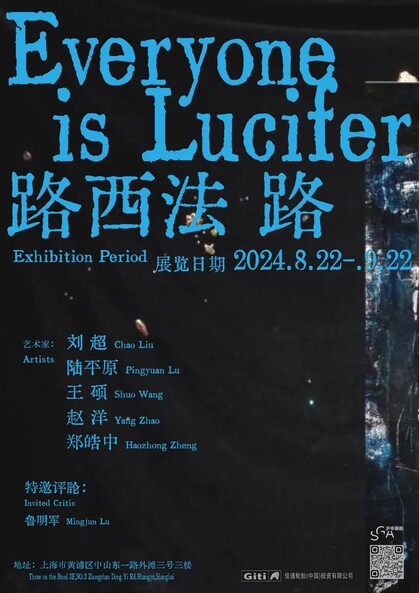

Group Exhibition Space & Gallery Association, Shanghai

Artists:

Liu Chao

Lu Pingyuan

Wang Shuo

Zhao Yang

Zheng Haozhong

Lucifer comes from Roman mythology and refers to “Lucife”, the god of the morning star. It was later translated into Latin as “Lucifer”. “Lucifer” is composed of lux (light, alliterative lucis) and ferre (bring), meaning “light-bearer”, the most beautiful angels. However, in later misinformation, “Lucifer” often referred to Satan, the devil, before he was expelled from heaven, and over time it even became one of the synonyms for Satan. For example, in Dante's Divine Comedy, Lucifer is portrayed as Satan, who rebelled against God and was expelled from the heavens and fell into hell.

Whether Lucifer was an angel or a devil, an angel who became a devil or a devil who became an angel, or even if it was originally fluid - an angel at one time, a devil at another, we do not know. In his classic book The Lucifer Effect: How Good People Become Demons, American psychologist Philip Zimbardo explores whether the norms and constraints scripted by the social roles of daily life can cause us to unknowingly do unbelievable things to other people, just like God's favorite angel, Lucifer, who fell to become the devil”. Philip Zimbardo's research focuses on isolated cases such as the Stanford Prison Experiment, which he conducted in 1971, but, if we put aside extreme experiments such as these, we find that often, especially today, this seems to be the norm, we are all on the Lucifer's path, and that everyone is Lucifer.

In his book, Zimbardo writes: “The humanizing relationship is the I-Thou relationship, while the dehumanizing relationship is the I-It relationship. With time, the dehumanizing doer becomes engulfed in the experience of human negativity, causing the 'I' to change and giving rise to the 'It-It' relationship between object and object or between doer and victim.” Here, the author poses a more pointed, and challenging, proposition: how are we to understand human nature today? Or even, will Lucifer become another reality apart from human (sexual) nature? For example, can we recognize Lucifer as an angel and Lucifer as a devil? Can we be conscious of our own Luciferian Split? And then, for example, using a particular powerful discourse, when we do not necessarily realize that we are forcing others to do so and so, especially without any legal risk or moral obligation, perhaps it is not the other person, but we who have become Lucifer? Zimbardo says, “Dehumanization knows no boundaries. ...... Turns victims into an abstraction, even giving them a demeaning name: 'cockroaches' - A species that must be exterminated. A more realistic way to put it is to imagine painting the enemy's face with nasty colors and then destroying the ‘canvas'”. But at this point, it is not necessarily the object that is the “canvas” that is destroyed, but also ourselves.

As a matter of fact, before deciding to use “Everyone is Lucifer” as the title of the exhibition, I did not have any communication or discussion with the five participating artists, but was completely driven by the psychology of their common style, and came up with the title in the first place. I trusted my judgment, and the collective approval of the five artists in a sense confirmed my judgment. Moreover, I knew that what they cared more about - and what I focused on exploring - was not how to paint a good picture or how to effectively express an idea, but the situation and mission/fate of the painting, the painter/artist, and even all people.

Liu Chao and Wang Shuo are two artists from Northeast China. They are couples, and also classmates. It is not difficult to imagine their mutual influences on painting methods and styles, but at the same time, one can also see their efforts to (deliberately) distance themselves from each other. Their paintings are both about the shaping of human beings, but they are presented as different directions and paths. In Liu Chao's paintings, both men and women, front and back, are abstracted into simple black or white silhouettes, as if they were ghostly shadows floating in an inexplicable landscape or obscure surface. At any moment, they may break away from the picture, or they may disappear into the background or the paint used as a medium. In his recent works, Liu Chao repeatedly depicts the same gesture of the same (unrecognizable) figure in different ways, exploring the infinite potential of an everyday bodily movement, which under his brush could be a beam of white light, a cloud of gray mist, a mountain, a cluster of fireworks, or become a corner of a garden. ...... Instead of placing the figure in a natural motif, he Instead of placing the figure in the natural subject matter, it is more like converging the body into the medium of painting. Perhaps Liu Chao does not realize that depicting or rehearsing the same action or (endlessly) repeating the same language over and over again is itself a practice of dehumanization. But Liu Chao is not all about repetition. What he values more is the difference in repetition, or the possibility of change as a body-medium, especially its dissonance and incompatibility, such as pulling out more spatial/temporal dimensions from the flatness of compulsion or oppression. However, most of the time, the artist in the painting faces an impenetrable wall - flatness - and even if there is a horizon, the artist is unable to reach the far distance, but is “blocked” in front of the mountain (“Mountain”, 2023). At this point, we might as well imagine the repetitive figure in the painting as a projection of the artist's self, just like “Lucifer”, today's artists need to play different roles - sometimes “angel” and sometimes “devil” - to adapt to institutional and ecological changes.

If Liu Chao's depiction is an attempt to extract (or pull out) the figure from the background/substrate of the picture, then Wang Shuo's depiction is more like “banishing” or “destroying” the figure from the background/substrate (“shape”). Wang Shuo customarily uses sweeping or semi-rotating expressive brushstrokes to give the images a kind of rising potentiality. “In Traces of Light” (2022), the “spinning” figures are transformed into beams of light. “Fluorescence” (2023) is like a “faraway landscape”, and the trees in “Snowbaby” (2023) and “Dancing Tree” (2024) are like flames. ...... These unique treatments on the one hand blur the relationship between the figure and the background, and on the other hand, bring the viewer outside the painting into the painting with her brushstrokes and compositions. The most frequent scene in her recent works is that of a dance between a man and a woman eating and drinking, with some of the images maintaining a high saturation level (e.g., Nocturne, 2021; Twilight, 2021; etc.), while others are intentionally low (e.g., Embracing, 2023), especially the enlarged male figures in the paintings showing their “richness” and “idleness”. In particular, the enlarged male figures in the paintings are “rich” and “idle”, sometimes in the mountains, sometimes in the square ...... They are exiling themselves to their heart's content, and at the same time, they are on their way to “destruction”. Wang Shuo enjoys the feeling of being “wild” on the canvas - blooming colors and humanity, but at the same time, just like the characters in her paintings, she often falls into the void.

Accordingly, Zheng Haozhong's recent works are also devoted to exploring the relationship between the figure and the background. For example, in “A Study on the Speed of Leaves” (2023), the woman in the painting is almost integrated with the scattered plants (leaves, branches, etc.), and at this point, it is useful to imagine the figure's body as a tree trunk. However, in another series, “She and the Tree Outside the Window”, the branch jumps to the front and distances itself from the figure behind it, whose silhouette and image can be vaguely discerned through the gaps in the branch. Through the gaps in the branches, the silhouettes and images of the figures are vaguely discernible. The branches are shrouded in the night, while the figures behind them seem to be basking in the sunlight. This appears to be within a single visual space - it conforms to the basic principles of perspective - but it is actually a superposition of two times. As always, Zheng Haozhong maintains a relaxed or almost “collapsed” state, and even he has difficulty distinguishing between such an “ordinarily” and “careless” way of creation Whether it is a daily behavior or a kind of artistic performance, but in any case, he never forgets to slyly peep or squint at the light and dark places of human nature.

Zhao Yang says, “People in darkness often have their hearts set on light.” But in reality, darkness and light are often not distinct. Zhao Yang depicts more of his childhood fairy tale imagination, which was originally an innocent and romantic scene, but in his writing, it is more absurd, funny, violent, killing, rotten, and barbaric...The gray and pink tone is also out of place with his childhood fairy tale imagination, and instead, there is a hint of melancholy, despondency, and uninhibited ... Perhaps the childhood fairy tale is just a pretext, those exotic dense forests, mountain streams, and wildernesses are both the heterotopia of imagination and the allegory of the cruel reality. "There are both mythic and real attributes, and also manifested in existential truths that are very different from those usually imagined.”

Fairy tales and games have been one of Lu Pingyuan's creative themes for a long time, and even in his new work, the “Best of the Best Draw” series, the color of the games is also present. Here, he collaborates with AI, paper-cutting, painting, and other media. On the one hand, he gives himself away, entrusting the generation of images to AI, and on the other hand, he returns to himself through meticulous cutting and depiction, attaching his perceptions, emotions, and temperatures to them. As a result, these images are full of innocent childish fun as well as fear of gods and ghosts, and in his opinion, this is “a huge fantasy world parallel to reality”. But Lu Pingyuan's concern is not only with the result but also with the unprecedented will and potential unleashed in the process when technology (the subject) encounters the will of man (the concept), including the tug-of-war between the two. Here, the real question/problem is whether technology makes human beings become devils, or human beings make technology become devils, or both were originally devils-Lucifer?

Three years ago, at the invitation of SGA, I curated the group exhibition “The Dance of Mephistopheles” (2021). The exhibition reiterated the “revolution of nothing” and the possibility of the avant-garde through the discussion of topics such as “psychopolitics” and “spiritual politics”. Three years later, following the steps of Mephistopheles, we are once again on the “Everyone is Lucifer”. What can an artist do on this road of no return? What can a painter do? What can people do? The five artists have given their respective answers, but my ears cannot help but ring again with Goethe's famous line in Faust: “Even if a man wants to sell himself, he will find that he has nothing in the end.”

Article: Lu Mingjun