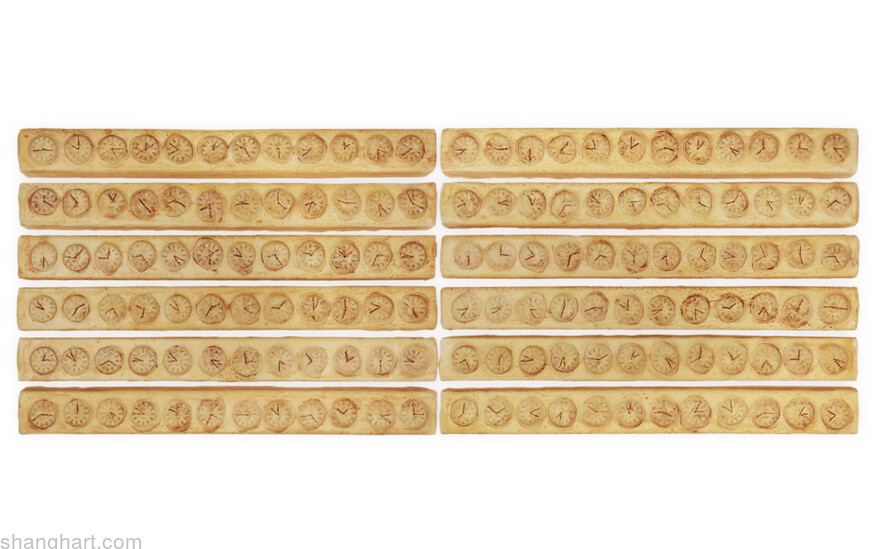

The clock faces set to multiple different times serve as a metaphor for life being fragmented into countless parallel schedules, each required to align precisely with specific checkpoints. These “timetables” include the social clock (e.g., the so-called optimal age for childbirth), the biological clock (e.g., forcing oneself not to stay up late), the work clock (e.g., submission deadlines), the personal life clock (e.g., planning ahead to catch a flight), and the cultural clock (e.g., the seventh day after a funeral, the stroke of midnight on New Year’s Eve), among many others. Yet “time” itself is a human invention, and the timetable is likewise a constructed device—one that fosters, in some individuals, a deep anxiety about time. A thousand seconds may sound like a long stretch, but it is in fact only a little over sixteen minutes—barely enough to accomplish much of anything.

Because these timetables are constructed rather than natural, many of the configurations of hour and minute hands on the clock faces could never exist in reality, thereby suggesting the notions of time as both “idling” and “fiction.”

Detail pictures: